Political Views of Employees of AI Companies

In the debate about artificial intelligence, there is the argument that it is virtually impossible for policymakers to understand the complex nature of AI, let alone to regulate it efficiently, timely, and properly. Instead, more and more people place their hopes for the responsible development of AI technologies in AI developers themselves. In other words, self-regulation.

Indeed, the trailblazers of AI seem to have accepted that their role is not only to open the Pandora’s box of AI but also to anticipate and prevent the negative consequences. In 2016, a consortium of tech giants – including Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, and IBM – founded Partnership on AI. Its mission is to develop best practices for artificial intelligence systems and to educate the public about AI. Alphabet’s DeepMind has even established a research unit to “help technologists put ethics into practice, and to help society anticipate and direct the impact of AI so that it works for the benefit of all.” But what is ethical – or a societal benefit – depends on who you ask. Naturally, when the fate of AI technologies is left to the discretion of the AI firms themselves, the ethical principles that guide these firms become a key issue.

Political campaign contributions provide a lens through which it is possible to explore the ethical principles of people working for AI firms. By tracking donations from individuals to their preferred political candidates, the worldviews and opinions of people can come to light. According to U.S. campaign finance law, “each contribution that exceeds $200, either by itself or when added to the contributor’s previous contributions made during the same calendar year” must be disclosed. The disclosure record must include the donor’s name, address, occupation, and employer, in addition to the amounts and beneficiaries of the contributions. During the election cycles of 2016 and 2018, almost 26 million private contributions from two million U.S. citizens were disclosed.

From this massive collection of contributions, all those made by employees of the thousand largest American corporations were selected (see “Methodology” for more details). These corporate giants were, in turn, divided into two groups. One is the group of “AI firms.” These thirty-one enterprises do not only primarily operate in the technology sector, but they are also on the list of organizations with most registered AI patents. The group of AI firms features companies such as IBM, Microsoft, Alphabet, Intel, Amazon, and Facebook. The second group comprises all the other corporations. What is being analyzed here is how campaign contribution patterns differ between employees of these two groups of corporations. This offers an insight into the political and ethical compass of employees of AI firms – the people who shape the future of AI.

Party identification gives a strong clue. Each donor was assigned a score of partisanship. It was calculated by dividing the total amount contributed to Democratic candidates by the total amount contributed to both Democratic and Republican candidates. The score ranges from 0 to 1, 0 if the person only donates to Republicans and 1 if the person only donates to Democrats.

As telling as it may be, party identification only gives a rough indication of the direction in which someone leans. To drill deeper, political candidates were assigned a set of grades on various issues. These grades were collected from ratings published by interest groups. A grade is meant to capture how well a politician promotes the legislative and political agenda of an interest group. Like partisanship, a grade can vary from 0 to 1. 0 denotes a conservative position on the issue, 1 a liberal position. Table 1 lists the selected ratings. Every donor was given a score for each issue, by calculating the average grade over the candidates he or she supports, weighted by the amount of each contribution.

Table 1: Description of ratings.

2019-09-24

* The rating was reversed to fit the scale where a higher grade entails a more liberal stance.

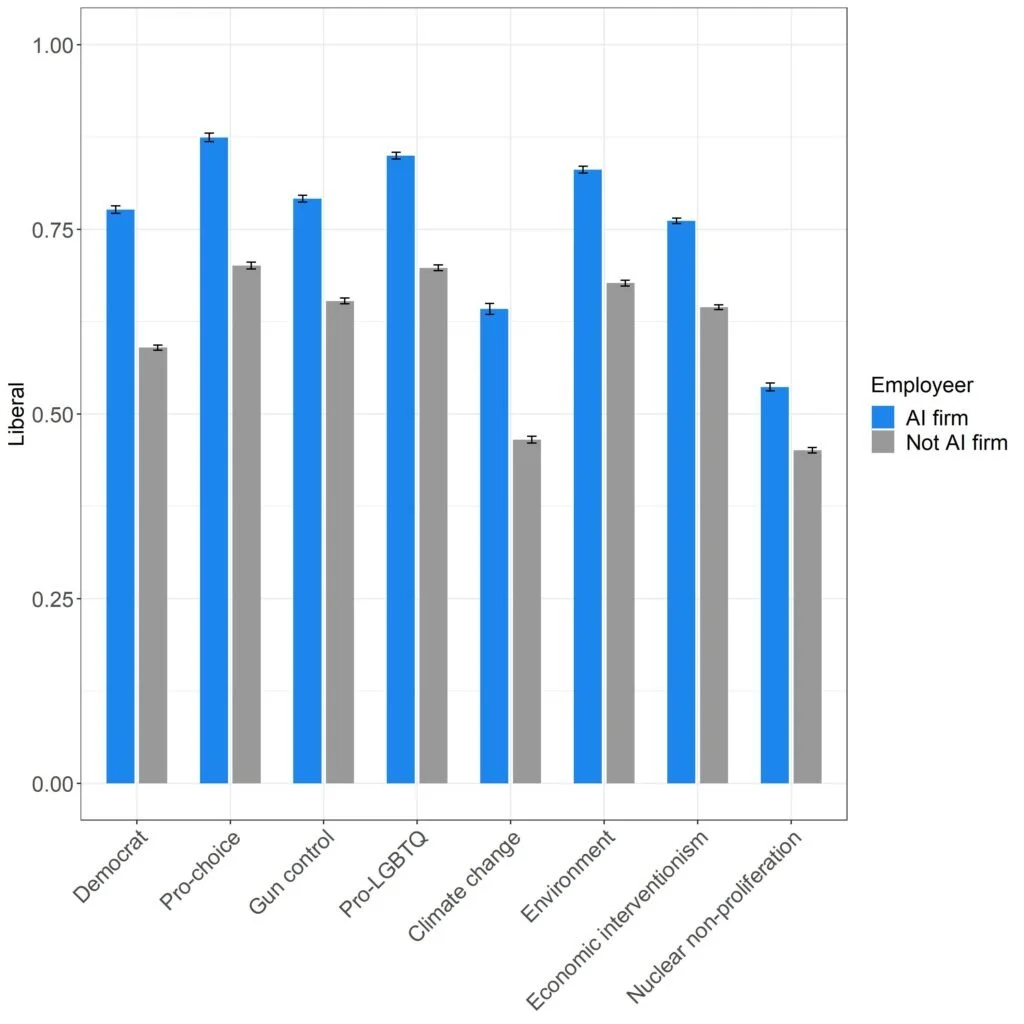

Figure 1 shows how employees of AI firms compare to employees of other large corporations when it comes to their preferred politicians. As can be seen, employees of AI firms support a more liberal agenda across the board. A conspicuous manifestation of this is the difference in partisanship. During the election cycles of 2016 and 2018, the typical employee of an AI firm gave 78 percent of her campaign contributions to Democrats and only 22 percent to Republicans. The same numbers for non-AI firms were 59 percent and 41 percent.

Figure 1: Average positions of political candidates supported by employees of AI firms and employees of other firms. A higher score indicates a more liberal position (95 percent confidence interval).

Because the ratings have their own methodologies and distributions of scores, it makes more sense to focus on the spread within categories. The largest differences between employees of AI firms and employees of other large firms can be observed vis-a-vis pro-choice and climate change. The politicians supported by employees of AI firms receive, on average, a 17 percent more liberal grade on climate change and pro-choice. The smallest differences concern economic interventionism – the view that the state has a role to play in the economy and in the redistribution of resources – and proliferation of nuclear weapons.

If the men and women of AI firms are much more likely to support Democratic candidates, it is not really a surprise that all the blue bars are higher than the grey ones in Figure 1. To account for this, the donors were put into regression models with their scores on the various issues as dependent variables and with partisanship and employment in an AI firm (set to 1 if true, otherwise 0) as independent variables. This gives the following interpretation of the results: Given the partisanship of a person, is employment at an AI firm associated with a more liberal position on the issue?

The answer is yes. As Figure 2 shows, six out of seven estimates are positive. In other words, if two people exhibit the exact same level of partisanship – whatever it may be – the one who works for an AI firm is likely to support a more liberal candidate than the person who works for a non-AI firm. This goes for abortion, gun laws, LGBTQ, climate change, environment, and economic interventionism.

Figure 2: The effect of employment in an AI firm on the support given to political candidates, with the partisanship of the donor held constant. A more liberal position taken by the political candidate is associated with a positive estimate (95 percent confidence interval).

The only exception to the rule has to do with the proliferation of nuclear weapons. It does not mean that the employees of corporations that invest heavily in artificial intelligence are unconcerned about nuclear proliferation. Graph 1 shows that the average grade received by candidates supported by employees of AI firms is above 0.5. Still, when controlled for partisanship, their contributions go toward candidates with weaker liberal profiles on this issue.

In brief, the corporations that lead the AI revolution exhibit a strong liberal tendency, judged by the politicians preferred by their employees. For those who hope for self-regulation of AI technology in accordance with liberal values, this is good news. Yes, it is hard to extrapolate these observations into specific hypotheses about the future of AI. At the same time, they do suggest that people inside the AI firms will favor technology that, for example, promotes environmental sustainability and does not discriminate against same-sex couples.

These findings are consistent with earlier research on the political dispositions of technology entrepreneurs. However, unlike these studies, the results here suggest – based on the progressive attitudes about economic interventionism – that there is no widespread hostility against government regulation and interference in the free market. On the contrary, employees of AI firms support political candidates with progressive economic agendas. Therefore, the very notion that AI firms will fight tooth and nail to avoid being regulated might be partly unwarranted.

Of course, the power over the development and implementation of AI technologies is not equally distributed among employees. The analysis presented here does not discriminate between Sundar Pichai, the CEO of Google, and the person who serves him food in the cafeteria inside the Googleplex. If both have given contributions larger than $200, they are equally treated as “employees of AI firms.”

In next week’s blog post in this series, the attention will shift to the upper echelons of AI firms. Do top managers differ from the rest of the workforce? And do top managers of AI firms differ from other corporate leaders? If the supervision of AI is left to the men and women who are at the helm of AI firms, understanding their values is vital to understanding our future.

See you next week.

Download related files